In the vast and complex landscape of modern industrial safety, the safety valve is universally revered as the "Last Line of Defense" for pressure vessels. Every time it lifts, it stands between asset preservation and catastrophic failure; between operational continuity and the endangerment of human life.

However, from conventional steam boilers to extreme supercritical high-pressure environments, engineers are constantly faced with a classic selection dilemma: Should one rely on the time-tested, rugged simplicity of the Spring-Loaded Safety Valve (SLSV), or embrace the high-precision technology of the Pilot-Operated Safety Valve (POSV)?

This decision is far more significant than choosing a component part number. It represents a fundamental clash between two engineering philosophies: "Direct Action" versus "Indirect Control."

I. Working Principle: The Physics of Direct Action vs. Indirect Control

To understand the selection criteria, we must first dissect the physics at play.

The Spring-Loaded Valve: Brute Force Equilibrium

The working logic of a Spring-Loaded Safety Valve is elegantly simple and somewhat brutal: Spring Force vs. Medium Pressure.

This is a typical direct-acting structure. The closing of the valve disc relies entirely on the mechanical pre-load of a heavy-duty compression spring.

Normal State: When the system pressure is below the set value, the spring force dominates, pressing the disc tightly against the nozzle seat.

Relief State: Once the medium pressure breaches the critical threshold (set pressure), the upward force of the fluid overcomes the downward force of the spring. The disc is forced open, allowing for full-flow discharge.

Closing: As pressure drops, the spring reasserts its dominance, pushing the disc back to the closed position.

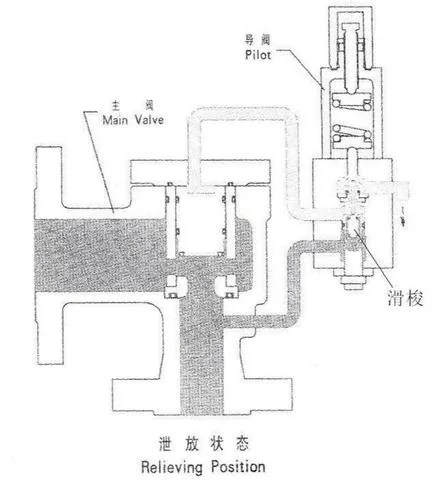

The Pilot-Operated Valve: The "Brain and Muscle" System

In stark contrast, the Pilot-Operated Safety Valve functions more like a sophisticated control loop. It employs a "Main Valve + Pilot Valve" dual-stage logic, utilizing the principle of "using the medium's own force against itself."

The Pilot (The Brain): This is a small, direct-acting valve that senses the system pressure.

The Main Valve (The Muscle): This is usually a piston or diaphragm valve that handles the actual discharge.

The Magic of Dome Pressure:

During normal operation, the system pressure enters the main valve inlet and is also fed (via the pilot) into the "dome" area above the main valve piston. Since the piston area on top is larger than the seat area at the bottom, the higher the system pressure gets, the *tighter* the main valve seals. This is counter-intuitive but brilliant.

When the system pressure hits the set point, the tiny Pilot valve snaps open (or vents the dome). The pressure holding the main piston down collapses instantly. The system pressure below then blasts the piston open, achieving immediate full lift.

II. Structural Features: Compact vs. Modular

Spring-Loaded: The Monolith

If you dismantle a spring-loaded valve, the core components are few: the Valve Body, Disc, Spindle, Spring, and Adjusting Screw.

Physical Advantage: This integrated design offers significant durability. There are no external sensing lines to break and no tiny orifices to clog.

The Size Penalty: As pressure and pipe size increase, the spring required becomes massive. A high-pressure, large-diameter spring valve can be incredibly heavy and tall, requiring significant headroom for installation.

Pilot-Operated: The Modular Machine

The POSV exhibits a complex mechanical aesthetic. It is essentially a modular system comprising the Main Valve (Piston/Diaphragm type) and the Control Pilot.

Design Highlights: Features often include non-flowing pilots (to protect the internals from dirty fluids), backflow preventers, and field-test connections.

Space Efficiency: Because it uses system pressure rather than a massive spring to keep the valve closed, the main valve is significantly lighter and lower in profile. For offshore platforms where weight is a premium, this is a game-changer.

III. Performance Showdown: Response, Sealing, and Capacity

This is where the engineering trade-offs become most apparent.

1. Action Characteristics (The "Pop")

Spring-Loaded: Suffers from the "Simmering" effect. As pressure approaches the set point (90-95%), the spring force barely equals the pressure force, causing the valve to "simmer" or leak slightly before it pops. It typically requires a 10%-20% blowdown (difference between set pressure and reseating pressure) to close properly.

Pilot-Operated: Exhibits "Snap Action." Because the closing force *increases* as pressure rises (up to the set point), there is no simmering. The valve opens fully and instantly at the set pressure. The blowdown can be adjustable and incredibly tight, often less than 5%, saving valuable product.

2. Sealing Performance

Spring-Loaded: As system pressure rises, the net force holding the seat closed *decreases*. This makes it prone to "pre-release leakage" or "simmer." Furthermore, in high-temperature applications, metal springs can undergo relaxation or creep, altering the set pressure over time.

Pilot-Operated: The logic is inverted. The sealing force *increases* as the system pressure rises toward the set point. Combined with soft goods (O-rings/elastomers), this allows for bubble-tight shutoff even at 98% of the set pressure.

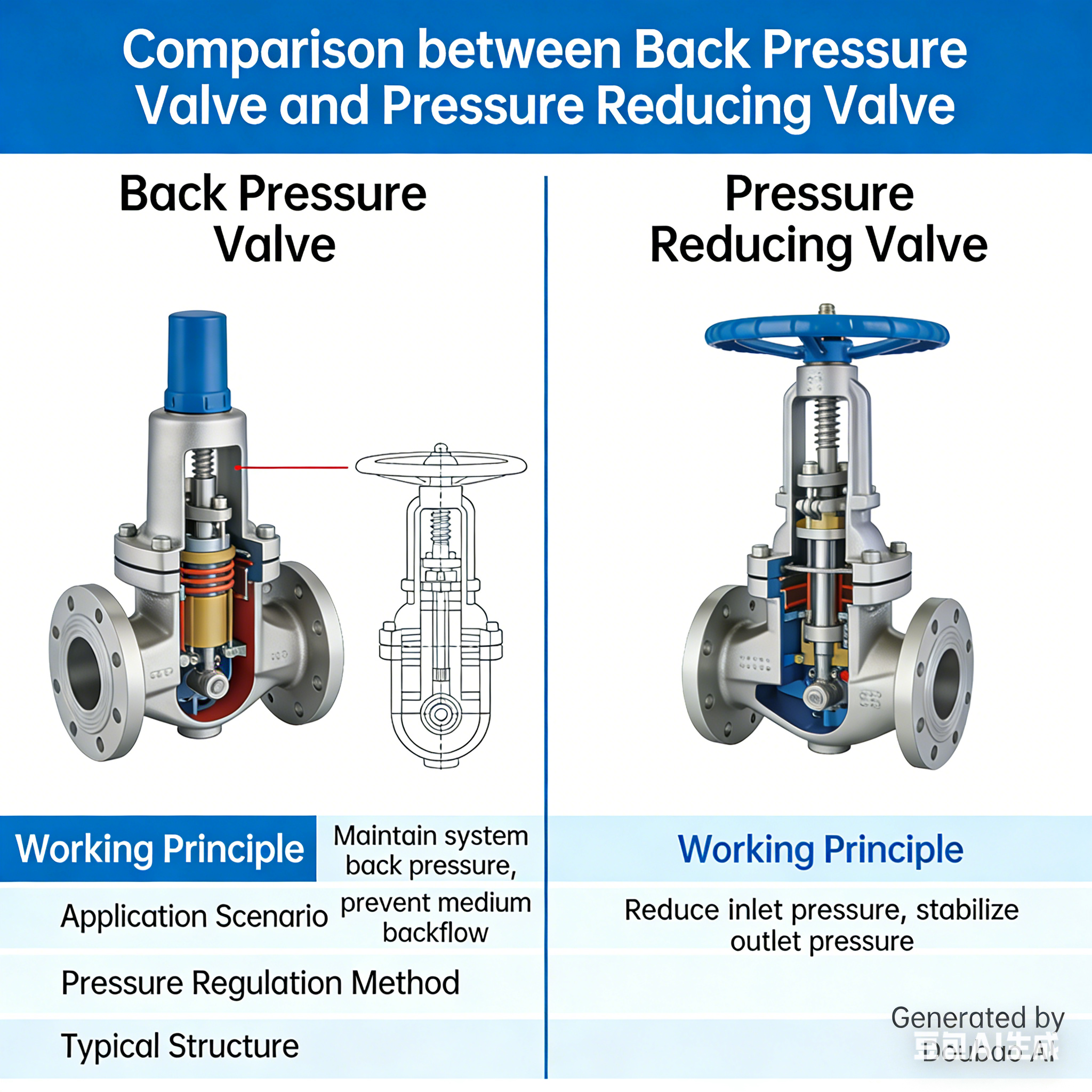

3. Back Pressure Sensitivity

Spring-Loaded: Highly sensitive to back pressure (pressure in the discharge piping). Variable back pressure can dangerously alter the set point or cause valve "chatter" (rapid opening and closing that damages the seat). Bellows can mitigate this, but only to a limit (usually 30-50%).

Pilot-Operated: The dome is referenced to the pilot, not the discharge. Therefore, POSVs are inherently balanced against back pressure. They maintain stability even when back pressure fluctuates wildly.

IV. Application Scenarios: Where Do They Belong?

The choice ultimately depends on the specific operational environment.

Typical Applications for Spring-Loaded Valves

The Spring-Loaded valve is the "workhorse" of the industry. It is favored for:

Steam Boilers: Code requirements (ASME Section I) historically favor the direct mechanical reliability of springs.

General Utility: Air compressors, water lines, and non-critical hydrocarbon service.

Dirty/Viscous Fluids: Since there are no tiny sensing lines or pilot orifices to plug, they handle slurry and dirty crude much better.

High Temperature: Metal springs handle extreme heat (up to 500°C+) better than the elastomers found in pilot valves.

Typical Applications for Pilot-Operated Valves

The POSV is the "specialist" for high-performance needs:

LNG and Cryogenics: The tight seal prevents valuable gas leakage and icing on the seat.

High-Pressure Pipelines (DN300+): Significant weight and cost savings compared to massive spring valves.

High Operating Pressure Ratios: When you need to operate the system at 95% or 98% of the valve's set pressure without leakage.

High Back Pressure: Essential for complex flare headers where back pressure varies significantly.

V. Maintenance Strategies: Reliability Management

Reliability is defined differently for each type.

Maintaining Spring-Loaded Valves

Focus: Preventing "Drift" and "Chatter."

Key Tasks: Periodic calibration of the spring (setting), lapping the metal seats to remove scratches, and checking for spring fatigue or corrosion.

Challenge: Large valves are difficult to remove and transport for bench testing.

Maintaining Pilot-Operated Valves

Focus: Preventing "Clogging" and "Aging."

Key Tasks: The pilot is a precision instrument. The primary failure mode is the clogging of the sensing line or the pilot filter. Elastomers (O-rings and diaphragms) have a shelf life and must be replaced regularly.

Advantage: Field testing is easier. You can often test the pilot set pressure without disrupting the main process using a field test connection.

VI. Economic Analysis: CAPEX vs. OPEX

This is a calculation that requires looking beyond the purchase order.

In the realm of small diameters (DN200 and below) and standard pressures (<10MPa), the Spring-Loaded valve dominates due to low initial costs—often 50% cheaper than a pilot equivalent.

However, in high-value processes, the math changes. Consider a large-scale petrochemical facility:

Product Loss: A spring valve that simmers loses product. A pilot valve with zero leakage saves it.

Uptime: A pilot valve's ability to be field-tested without shutdown, and its resistance to chatter, reduces unscheduled downtime.

Case Study: In a recent ethylene project, while the initial investment for POSVs was 20% higher, the reduction in product loss and maintenance man-hours resulted in operational savings exceeding 1.5 million RMB over three years.

Conclusion

The Spring-Loaded and Pilot-Operated safety valves represent two distinct pinnacles of industrial design philosophy: "Simple Reliability" versus "Precision Control."

As industrial systems race toward higher pressures, larger capacities, and intelligent monitoring, the market share of Pilot-Operated Safety Valves is growing at an annual rate of 8%, steadily conquering the high-end market. Yet, in the vast ocean of general-purpose equipment, the Spring-Loaded valve remains the immovable bedrock.

For the modern engineer, the goal is not to declare a winner, but to understand the "temperament" of each. Finding that delicate balance between initial cost, maintenance capability, and performance requirements is the key to ensuring the industrial pulse beats steadily and safely.